Constructions of the Self and Reflexivity

This session, we concentrated on our roles as researchers and the benefits and limitations of locating the ‘self’ in research. I found this session especially valuable in thinking about locating the ‘self’ within textual analysis – a part of this discourse of which I was less aware.

We focused on three key texts which presented differing methods for deploying the researcher-self:

Hennegan, Alison. "On Becoming a Lesbian Reader". Sweet Dreams: Sexuality and Popular Fiction. Ed. Susannah Radstone. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1988. 165-90.

Taylor, Verta and Rupp, Leila J. "When the Girls are Men: Negotiating Gender and Sexual Dynamics in a Study of Drag Queens". Signs 30/4 (2005): 2115-2140.

Ward Jouve, Nicole. "Criticism as Autobiography". White Woman Speaks with Forked Tongue: Criticism as Autobiography. London and New York: Routledge, 1991. 1-13.

Following our reading of these texts we were required to write about our own researcher-selves. I chose to focus on my researcher-self in textual research, as this is likely to be the research area I will focus on in later work. Following my writing is a series of related questions which I will answer with a focus on the Hennegan text, as I did in the class discussions, but with elaborated thoughts relating to the other two texts, which I feel will benefit the work we did in group work during the seminar.

My researcher-self

Since beginning my MA in October I have become increasingly fascinated with the relationships which arise between researchers and subjects of research, whether that subject is a person, a text or another artefact.

My research background is in textual analysis and cultural research. Although this may seem rather limited, such research has brought me into contact with texts as varied as music, blogs, online chat, images and magazines. Although a lot of awareness has been raised about the influence a researcher can have on the research process through interviews or direct contact with the subject, I get the impression that there has been less awareness of the influence a researcher can bring to a textual analysis. I would like to outline the influences (and changes in influence) that I brought to a specific text - Jane Eyre - and what consequences this might have on any further research which I conduct on this text.

I first encountered Jane Eyre when I was 11 or 12; it was the first 'classic' I had ever read and I remember sitting on the roof of our garden shed in Scotland reading it in the sunshine. Although I had only 6 or 7 years of reading experience, I already had some awareness of the 'classic' genre, and as such I was aware that this book was different from other books I was reading at the time. It made me feel 'grown-up' to be reading what I considered to be an 'adult' book and I felt proud of myself for reading (and understanding!) a 'difficult' novel. The fact that I remember exact details about where I used to sit and read on those late summer evenings indicates that the experience of reading this novel was significant. As this was the first text I had read from that era (Jane Eyre was first published in 1847) I did not have any contemporary references, but in its portrayal of Jane's school-life, friends and love for Rochester, I found myself relating to the text in the context of my own modern-day experiences - although there were 150 years between myself and Jane, I identified with her experiences of bullying, unrequited love and ambition.

This experience stayed with me and almost four years later, when I came to studying Jane Eyre academically for the first time, it influenced the way I tried to academically understand the novel. I attempted to rationalise and explain Jane's actions by stating that 'Jane felt this way because that is the way I felt when I imagined myself in her situation' or 'she reacted understandably - that's the way I would have reacted to a similar situation in my own life'. My deep identification with Jane as a character also understandably influenced the way I interpreted the novel - if anyone in the class attempted to criticise her, saying she was 'weak', 'drippy' or 'dull', I felt obliged to defend her - almost as if defending Jane was defending my right to identify with her: it felt like I was defending myself. This academic reading explained the contemporary influences and references in the novel that I had, in all likelihood, misunderstood the first time I read the novel: I learned who the author was, the circumstances around the book's release and contemporary first impressions and reactions to the novel. Thus I probably gained a fuller reading of Jane Eyre, but again, these factors were explained to me by a teacher, who would have been taught by another person who would have studied and read critics who were informed by other critics, creating a chain of passed on knowledge. At the time though, the views of teachers were never 'wrong', so I accepted this authoritative information in order to then regurgitate it myself. Furthermore, there was a marked difference in the way I read Jane Eyre for pleasure and the way I read it for academic examination. Thus the knowledge I had about Jane Eyre at this point in my life was influenced not only by my own identification and wider reading, but by the influence of others' reading and (non)identification.

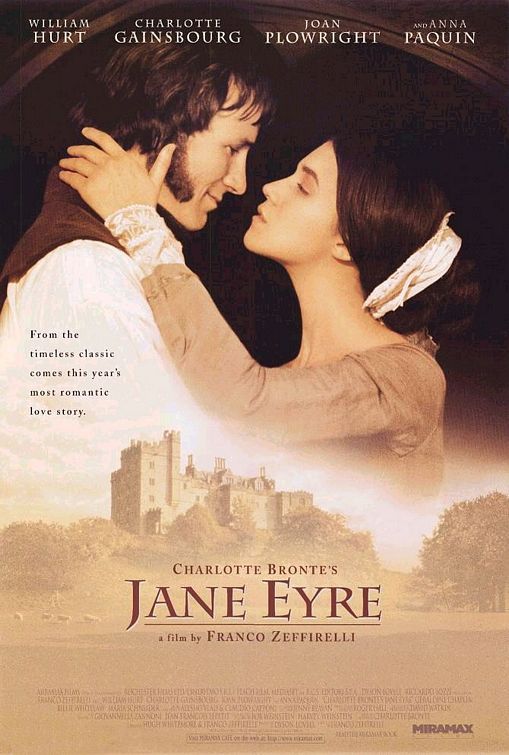

Recently, I have studied Jane Eyre academically for a second time, in conjunction with a reading of Jean Rhys' Wide Sargasso Sea. I re-read Jane Eyre rather nostalgically, re-living previous reading experiences however fleshing this out with the feminist knowledge that I had since gained through further education and wider influences (newspapers, TV, opinions of friends and relative). Because Jane Eyre is a very widely known and celebrated text, its cultural influences are widely available and accessible - I watched TV and film adaptations, caught references in more modern 'chick-lit' novels and I had a much greater historical knowledge of the time period (See image, from

Recently, I have studied Jane Eyre academically for a second time, in conjunction with a reading of Jean Rhys' Wide Sargasso Sea. I re-read Jane Eyre rather nostalgically, re-living previous reading experiences however fleshing this out with the feminist knowledge that I had since gained through further education and wider influences (newspapers, TV, opinions of friends and relative). Because Jane Eyre is a very widely known and celebrated text, its cultural influences are widely available and accessible - I watched TV and film adaptations, caught references in more modern 'chick-lit' novels and I had a much greater historical knowledge of the time period (See image, from

Going back to Jane Eyre after reading Wide Sargasso Sea I found I could not read it with the same identification I once had - I now found Jane to be a selfish and weak character and no longer wanted to identify myself and my experiences with her own. I also felt a bit foolish - surprised that I hadn't picked up on these markers of racism and discrimination before. However this new understanding and reading of Jane Eyre was ultimately borne out of my recent learning of nineteenth century racism and colonial contexts, knowledge which I had not had available before.

So reading Jane Eyre now, I cannot approach the text in an objective manner. All the history and knowledge that I have with the text cannot be unlearned and cannot be ignored. So an acknowledgement of the place of Jane Eyre in my own cultural learning and of myself within my reading of Jane Eyre, although it may not be objective, will allow for a recognition of multiple interpretations and will seek to avoid privileging one viewpoint over another. I occupy a unique position in relation to Jane Eyre and, for that matter, in relation to every text I have encountered. Thus I should always indicate an awareness of the multiplicity of interpretation and be aware of the potential influences in my own learning which will affect what I understand in what I read.

Some questions

- How was the researcher-self presented and deployed in each of the three key texts?

What did you learn from each text, and to what extent was this dependent on the self-conscious use of the researcher-self?

Hennegan is vociferous about the potential for multiple and resistant readings and this is clearly a skill which she inherits and develops through her ‘personal’ reading experiences. Furthermore the research which Hennegan and Taylor and Rupp go on to explore is (in their own words) almost directly related to their sexuality and their experiences of living as lesbians: Hennegan draws links between generations of confused adolescents to show how, just as her own memories can be re-interpreted in light of her contemporary knowledge and awareness, the meaning of ‘gay identity’ can also be re-interpreted; Taylor and Rupp pay particular attention to the interaction of themselves as lesbians with their subjects, although they also acknowledge interactions of class and educational differences.

What might have been obscured by the subjective voice?

It was suggested that Hennegan’s privileging of her sexuality as the primary marker of her researcher-self presents her sexuality as latent – she never challenges her sexuality, but accepts it as something which was always present and of which she had ‘inklings’ (167). This may prevent her from acknowledging how her reading may have shaped her and thus affected her researcher-self.

This led to a discussion of the problems surrounding using aspects of identity in research, and the potential effects this may have. When researchers are attempting to match aspects of identity, what is an important part of a researcher’s identity (i.e. what may affect the research) and what is not important (e.g. height)? Why do we privilege certain attributes over others? (e.g. Hennegan and Taylor and Rupp both privilege their sexualities as the primary aspect of their researcher-selves)

What different kinds of researcher-self did you wish to write into your own text?

I chose to focus on my relationship to one particular text as I felt it might be easier to illustrate my researcher-self in relation to one particular text. Thus I highlighted previous reading experiences and the ways they had altered my relationship to the text.

However the most significant aspect of my relationship to this text was, I realised, the fact that even upon my first encounter with this text, I was not approaching it outside of cultural knowledge or learning. I knew what genre of novel it was, the cover told me when it was written, I knew my mother and grandmother had both read it (but my father and grandfather had not) so even if I am only now able to vocalise this learning, I am profoundly aware of the impossibility of ever reading anything outside of a prior cultural (and perhaps social) teaching and learning. This realisation has altered the way I consider my relation to texts I encounter for the first time – e.g. who recommended them? Why did I choose to read this text? What is the text’s genre and what do I know about the genre?

- What were the specific challenges you faced when reading and writing these subjective texts?

As with any self-analytical writing, it is difficult to articulate your relationship with research, as it is often challenging to turn an analytical gaze inwards. Although I did find it difficult to acknowledge the extent to which my research is affected by my knowledge and learning (perhaps it is entirely affected), I also found it very liberating to trace the strands of my knowledge back and to accept their effect on me and my research. I also found it almost comforting, reading Hennegan’s enmeshing of her reading knowledge and her research, to be able to draw on personal reading within research and to fully appreciate the fluidity of my researcher-self and my more general ‘self’. In the end, it is not possible to extract my researcher-self, from my wider ‘self’, thus my research will necessarily inform me, just as my ‘self’ informs my research– it is not always possible to say where ‘me’ ends and my ‘research’ begins.

Reflections

Having already encountered Hennegan’s article in the first Debates session, I found it very useful to return to it in a slightly different way and to compare and contrast what I gleaned from the article then and the way I regard it now. Ironically, it is likely, but almost impossible to quantify, the influence that my first reading of Hennegan had upon this subsequent reading and interpretation.

However as I said in the first session, it is ‘useful to examine the way we change our minds about the texts through further education and change of context of reading and time’. This course has made me think much more critically about my own position in relation to my research and having gone through several more classes, I would refute the assertion I initially made that there may be a ‘potential for universal reading’. I would now argue that as our learning and experience is so central to our research and our selves, that there is no such thing as ‘universal’ reading and this, in fact, may be more harmful in our approach to literature. Recalling being taught the ‘right’ interpretation to texts by school teachers in light of my new knowledge of the impossibility of objective knowledge, I am more determined than ever not to replicate this universalising of knowledge in my own research by continuing to be sensitive and aware of my researcher-self.

No comments:

Post a Comment